On Fogo Island, Artists Celebrate the Extinct Great Auk

Published September 4th, 2024

Photography by Jennifer Bain unless otherwise noted

Like the penguin, it was a flightless seabird that was agile in the sea and vulnerable on land. Like the puffin, it was part of the Alcidae family of birds. Like the dodo, it went extinct on our watch.

But who among us knows about the great auk and its curious connection to Newfoundland and Labrador?

The people of Fogo Island sure do — especially this year with the inaugural Great Auk Celebration.

There was a World Ocean Day talk by an Icelandic author, a regatta where people raced punts (wooden row boats), and a Facebook callout for auk art. More than 70 pieces have been created so far, including poetry, paintings, songs, sculptures, clothing, quilts, placemats and replica eggs.

“We’re populating Fogo Island and beyond with images of the great auk,” Saltfire Pottery’s Fraser Carpenter, the sculptor leading the grassroots celebration, said during a community event. “All this work is bringing the great auk out of obscurity.”

The stubby-winged diving birds, with black backs, white stomachs and a white patch in front of each eye, stood about 2.5-feet tall and weighed about 11 pounds. Explorers dubbed these Pinguinus impennis “penguins” before transferring the name to similar looking but unrelated birds in Antarctica.

Great auks lived at sea around coastal Europe, Iceland, Greenland and Canada. The world’s largest known breeding colony was on Funk Island — a speck of granite in the North Atlantic Ocean just 60 kilometres east of Fogo.

Thousands, or perhaps tens of thousands, of auks came to land each summer to lay a single egg in this desolate place that seemed safe from animal and human predators. The Beothuk, an Indigenous people that once lived on Fogo, canoed to Funk to sustainably harvest auk eggs before they too were driven to extinction.

French explorer Jacques Cartier stopped at the guano-filled Funk Island in the 1500s to load up on auks, calling their numbers “so great as to be incredible” and describing how “these birds are so fat that it is marvelous.” For three centuries, the foul-smelling island served as “fast-food takeout” for Basque, French, English and Spanish mariners.

Once the world wanted silky feathers for mattresses and quilts, it was game over for the auk. Fogo Islanders were among those who helped harvest them and even built a crude shelter and stone corral on Funk Island.

Fishermen killed the last nesting pair (and trampled their egg) at Eldey Island, Iceland in 1844. There was an unconfirmed 1852 sighting of a single auk in Newfoundland’s Grand Banks, one of the world’s richest fishing grounds. Funk Island became the world’s largest great auk graveyard.

But Fogo Islanders never forgot the auk.

Realizing the global importance of both Funk Island and the last flightless bird of the northern hemisphere, the islanders helped seabird biologist Bill Montevecchi, a Memorial University of Newfoundland professor, launch an exhibition here in the late 1990s.

Then in July 2010 came a five-foot-six bronze auk at the end of the Joe Batt’s Point Trail. Created for American sculptor Todd McGrain’s Lost Bird Project to speak to the tragedy of modern extinction, this much-photographed auk gazes mournfully towards a matching statue across the ocean in Iceland.

Just after the statue unveiling, the Funk Island Great Auk Exhibition was renovated and upgraded. It’s part of the Fogo Island Marine Interpretation Centre in Seldom and is housed in a small “store” that was once used for fish nets and gear. Unlike the auks, the exhibition is “never over.”

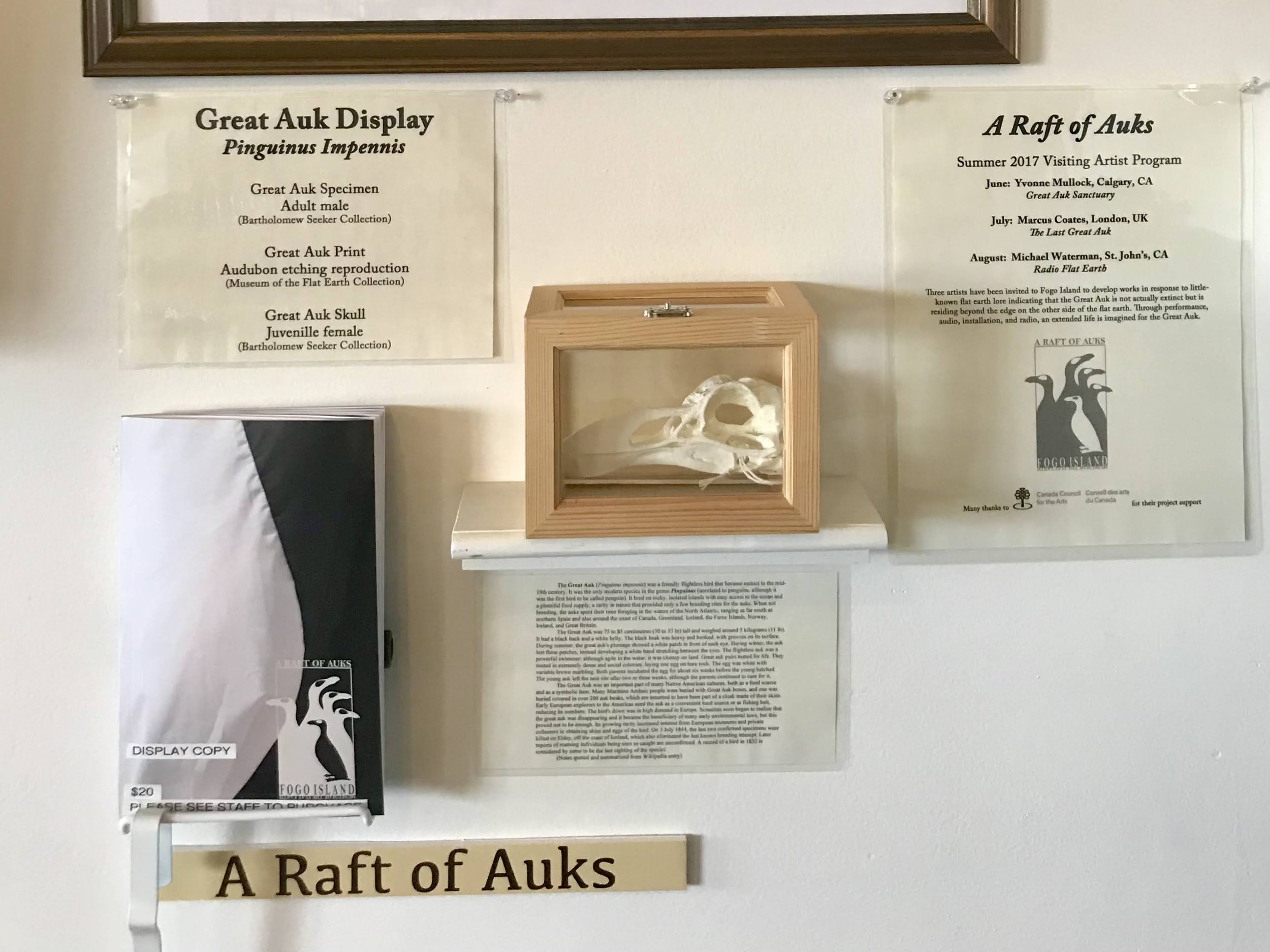

I first visited Fogo in 2017, the year that visual/performance artist Kay Burns used a Canada Council grant to run “A Raft of Auks” at her now defunct Museum of the Flat Earth in the Flat Earth Coffee Co.

Burns invited three artists to develop performances, installations, audio and radio works in response to “little-known flat earth lore indicating that the Great Auk is not actually extinct but is residing beyond the edge on the other side of the flat earth.”

I fell hard for auks and have stumbled upon traces of them around the world ever since.

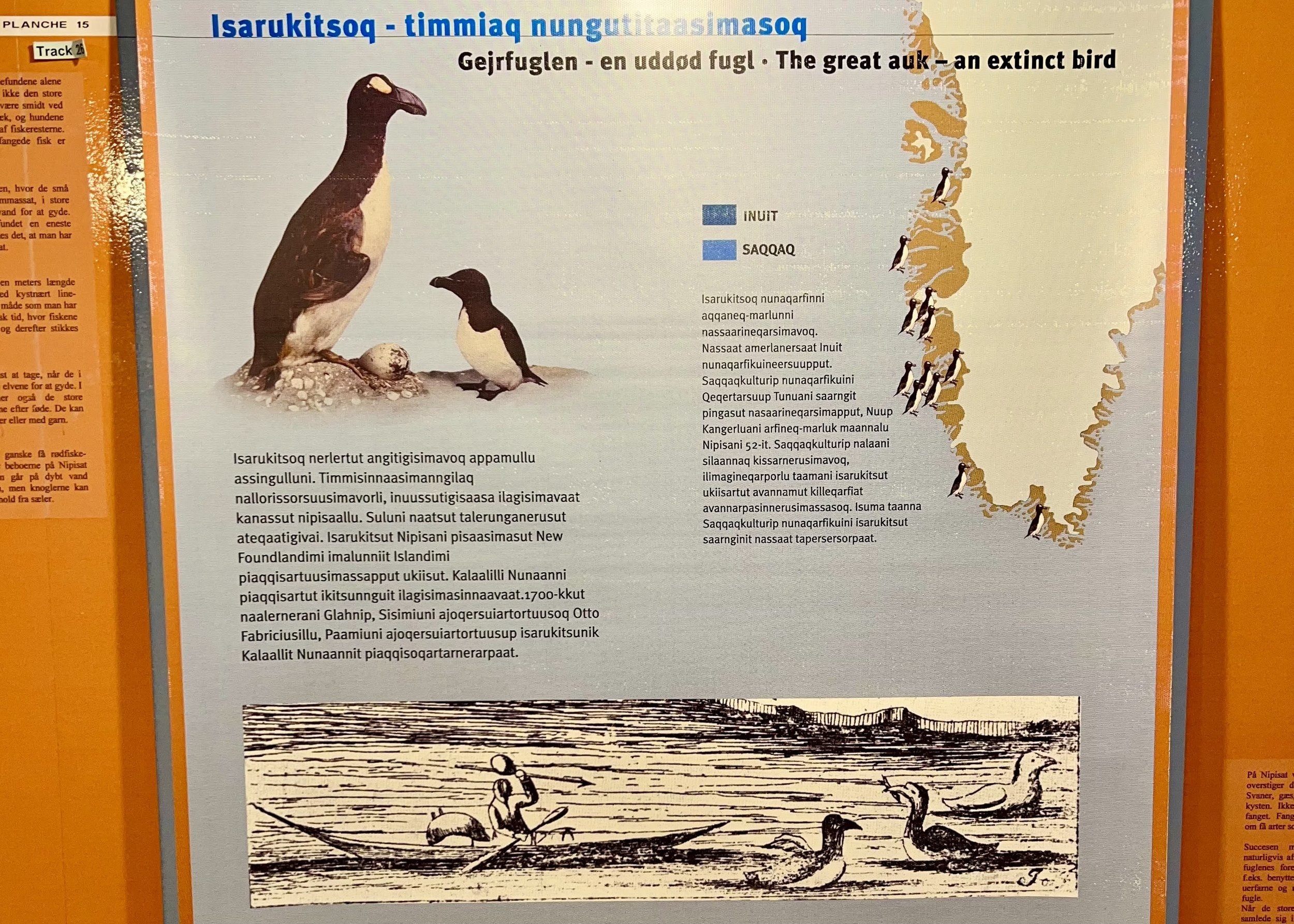

On an Adventure Canada expedition cruise, I gravitated to auk sketches at the Sisimiut Museum in Greenland. Only the words “the great auk — an extinct bird” were in English, but illustrations showed Greenlandic Inuit hunting them and a map showed a dozen spots where they were once found.

Great auks also frequented Rathlin Island in Northern Ireland. When I visited the RSPB Rathlin West Light Seabird Centre to see puffins, I learned how school kids had just delved into the auk’s sad history and had even gone to Trinity College in Dublin to see a taxidermied auk.

This summer, I made a beeline to the Rooms in St. John’s — Newfoundland’s largest cultural space — just to see a composite skeleton of an auk made from bones gathered by Montevecchi on Funk Island. He admits it’s “not as elegant” as he would like it to be.

I have yet to see the other composite skeleton that’s at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa. Or the intact Funk Island auk at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. As signage at the Rooms stressed: “All that remains of the Great Auk today are 81 mounted specimens, 24 complete skeletons, two collections of preserved internal organs and 75 eggs.”

Close to Fogo in Twillingate, Charlie Fendley has shown me the Durrell Museum’s colony of 11 life-sized, concrete replica auks. Artist Paul Summerskill donated the art installation to the community museum to teach people how quickly a species can become extinct.

I have also toured Twillingate’s Great Auk Winery, which calls the auk extinction “a travesty” and notes it was “the first time humans realized that they could extinguish a prolific organism from the face of the earth.”

On Fogo, there are auks hidden in plain sight in some of the island’s 11 communities.

In 2019, I photographed an intriguing interpretive sign that tells how two islanders captured a strange bird floating in ice along the shore in 1888. They cooked and ate it, while officials compared the head, feet and wings with sketches of the great auk.

“Opinion of the time left `no doubt’ that the bird was a Great Auk,” explained the sign, which seems to have vanished or been put in storage. “If so, where did it come from, and did an unknown colony of the auks still exist forty years after they were thought extinct? The mystery is unsolved to this day.”

In Stag Harbour, you can always see the wooden great auk that Harry Sheppard carved more than a decade ago. Anchored to a tiny rock near shore, it juts out of the ocean just off shore, even at high tide.

This summer at the Lookout shop in the town of Fogo, I scored a hooked auk coaster made by Dale Payne for the Great Auk Celebration. And at Wind and Waves in the Tilting Heritage Centre, I found Freeman Combden’s carved auk set on a piece of caribou antler.

Luke’s Landing — a seaside space newly created by Rita Penton in Joe Batt’s Arm — hosted a new Great Auk Regatta in July and erected a family of painted plywood auks made by Carpenter. The landing is across from Growlers so I like to admire the auks with a partridgeberry jam tart ice cream cone in hand.

I missed University of Iceland professor Gísli Pálsson’s World Ocean Day talk on Fogo in June, but packed his book — The Last of its Kind: The Search for the Great Auk and the Discovery of Extinction — for my summer visit.

“Prior to the killing of the last great auks, extinction was either seen as an impossibility or trivialized as a `natural’ thing,” Pálsson writes. He details how the “big, defenseless birds were herded like sheep into pens, gang-planked into boats, and clubbed to death” so the meat could be used as food and fish bait, the fat rendered down for its oil, and the feathers used to stuff quilts and pillows.

“Lost species remind us uneasily of humanity’s predatory behavior — and of lessons that we may not yet have learned,” Pálsson concludes.

It’s a warning that’s repeated by Montevecchi when he gives a talk at the “Bird House” (the nickname for the Funk Island Great Auk Exhibition space).

“I think Fraser (Carpenter), bless her soul, drew a lot of attention to this and you’re all here today,” Montevecchi told us. “I mean that’s a good thing — I didn’t think anybody would be here, so I’m totally surprised.”

He first visited Funk Island in 1977 to study Northern gannets, Common murres (turrs) and other seabirds. But on that granite rock outcrop that measures just 800 metres by 400 metres, Montevecchi found a grassy meadow and a rare auk graveyard.

“It’s a cemetery to an extinct species,” he said.

Since then, Montevecchi has made countless research trips to study Funk Island’s nesting seabirds. It’s five hours each way by longliner, and sometimes the weather is so treacherous he can’t land or gets stuck on the island.

“Yeah — it’s a marvellous, terrible place,” skipper Bill Sturge once said to him and the phrase stuck.

Montevecchi theorizes that the Beothuk, who revered the auk, came here on pilgrimages. “You didn’t come for a joyride, you didn’t come to collect eggs, you came because it was difficult. It was kind of like a rite of passage, maybe.”

People are surprised to learn that Newfoundland has two sets of Penguin Islands. One is near Musgrave Harbour (not far from Fogo on the northeastern coast) and the other near Ramea off the south coast. “Tourists who have never heard of the original penguin might wonder what hemisphere they’re in,” the seabird biologist joked.

We can’t go to Funk Island, though, since only scientific research is allowed.

It is now the Funk Island Ecological Reserve and protects one million murres — the world’s largest colony — as well as gannets, Northern fulmars, Atlantic puffins, Razorbills, Thick-billed murres, Black-legged kittiwakes, and Herring and Great Black-backed Gulls.

Auk lovers admit it’s hard to talk about a bird that’s extinct and an island that ordinary people can’t visit. “The great auk could still be here,” Montevecchi mused playfully. “I just can’t even imagine what tourism would be like if we had northern hemisphere penguins — but we don’t.”

What Newfoundland does have is the Little Fogo Islands. I’ve taken Fogo Island Boat Tours to this archipelago to see nesting puffins and more of the auk’s cousins like razorbills.

You’ll cruise by the great auk statue on your way in and out of the harbour. But still make time for the 90-minute round-trip hike to give the larger-than-life statue a hug.

“So even though we have a world-class bronze sculpture of the great auk at Joe Batt’s Point, and we have the Funk Island Great Auk Exhibition in Seldom, the great auk remains relatively obscure,” Carpenter lamented during a community potluck. “It’s up to us to bring it into our own times. It’s not easy to imagine a population of large flightless birds that had once numbered in the millions right outside our coast, so hence the Great Auk Celebration.”

Her January Facebook post asked “for anyone to do anything in any medium that referenced the great auk.” There were no rules, cash grants or plans to monetize the project.

“There are lessons to be learned from our past,” Carpenter said. “Perhaps to remind us of our responsibility to conservation and environmental stewardship.”

I’ve learned that you don’t have to literally kill every member of a species to wipe them out. You just have to kill enough of them so that the population loses its resiliency and goes into a death spiral.

The moral of the great auk story is that it’s up to us to prevent further extinction.

“What we see around us is not a forever status,” Carpenter warned. “Most changes in our environment are subtle. So what would a bird be that many people would miss from our lives today? The Atlantic puffin for one.” I shivered as I imagined the demise of the “clown of the sea” whose striped mating beak inspired the outrageous orange colour of my Fogo cottage.

Photo Credit: Great Auk Regatta/Paddy Barry

That potluck talk did end on an upbeat note.

The regatta will become an annual event to mourn and commemorate the great auk, and five whimsical auk costumes made by multidisciplinary artist Yvonne Mullock in 2017 for a processional requiem called Great Auk Sanctuary will likely keep being worn for it.

“So the great auk will definitely be remembered every year,” said Carpenter. “But we must do more.”